People greeted the earliest photographs with wonder and amazement because of their ability to faithfully reproduce reality. No other art form had enabled us to recreate nature exactly as it is, to provide us with a true and accurate record of an exact instant in time. Of course it wasn’t long before artists realized they could manipulate the image, so that it was no longer quite so accurate or true, but the world they shared was more interesting, more beautiful. In 1841 Henry Fox Talbot stated, “It would hardly be believed how different an effect is produced by a longer or shorter exposure to the light, and, also, by mere variations in the fixing process, by means of which almost any tint, cold or warm, may be thrown over the picture, and the effect of bright or gloomy weather may be imitated at pleasure. All this falls within the artist’s province to combine and regulate.”

And yet these manipulated images still retained the authority of every photographic image. We believe it because we see it, in print or on our computer screen, we accept that this really happened, at least some part of it. As James Agee wrote, “It is clear enough by now to most people that ‘the camera never lies’ is a foolish saying. Yet it is doubtful whether most people realize how extraordinarily slippery a liar the camera is.”

And it didn’t take long for these subtle manipulations to become more overt and more creative, for Man Ray to create a smiling sky, or Melies to make a trip to the moon. For artists to share with us new, beautiful, impossible worlds, which still seem, somehow, on some level, to hold on to that photographic truth.

Four Artspan photographers share their strange new worlds with us.

In Myselfportraits Ode to Icons and Other Absurdities, Sally Stockhold has created a series of portraits of accomplished women from history and fiction. She wanted to acknowledge some of these women and create a photographic narrative "using myself as the 'canvas' to depict them.z' In another series, The Life I Never Lived, she imagines the crazy amazing times in New York City between 1964 and 1986, experiences she missed out on, and she puts herself in the middle of the action.

She creates every part of these worlds, “I play every character in my photographs. After research on each project, I paint the backdrop, assemble props, wigs and costumes, and make the photograph.

“The camera is mounted on a tripod and locked down with strong tape and sandbags so it doesn't move. The focus and lighting are set by me. My sister Kathleen or one of my daughters will press the camera button and take about 12 photos at a time in different poses. I then step out of the set, examine the digital photos and decide if I’ve captured the part of the scene as imagined. (There are a lot of laughs during this process. Sometimes I ruin my make-up, or my wig falls sideways or I forget to take off my glasses, or even knock over a prop).

But I keep reshooting until the photo works for me. There can be 12 takes or 75 for one character. Depending on how many people are portrayed in a story, the photo process can sometimes take two days or more. When the entire shoot is finished, the characters are “stitched” together in Photoshop and a print is made. Then I selectively hand-color the photograph with pastels and prismacolor pencils and, Voila, it’s done!

As with all my photos, I make up the idea in my head, there is no evidence that Janis or Jimi ever jammed at the Chelsea although they both stayed there while in New York. The "Doppleganger Twins" I created because Diane Arbus among many other topics, photographed many people from the circus.

Over the many decades since the earliest photographs, methods to manipulate photographs have become increasingly subtle and complex. But in their slickness and tidiness, they lose some of the magic and unexpected beauty of older photographic methods. Laura Bennett describes her methods as “old school.” She works primarily with black and white film and with medium and large format cameras. Her equipment is large, heavy and cumbersome, “and quite wonderful!” She develops all of her film in the darkroom, where she plays with chemicals to produce strange and beautiful effects.

“Robert Adams said something once about how your hands can sometimes learn what the mind cannot.

“I like that."

“My work addresses the female experience and the spaces between birth and death. As a mother of nine children, I am comfortable with that.”

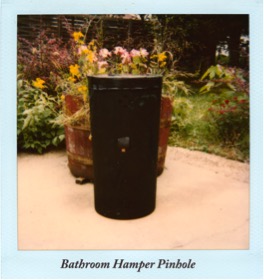

Valerie Burke works with pinhole cameras, which she makes herself, and with which she captures mysterious and beautiful images. “The pinhole camera is know for its long exposures, depth of field, and surprise effects.

“Pinhole cameras hide secrets like a magic genie. Focus, time, lighting is altered because of its simple construction. There is no viewfinder, so the information entering the ‘camera’ becomes stream of consciousness; there is no shutter, so time becomes flexible and there is no advance mechanism so one image can overlap the next; it becomes cinematic–ghost like. The camera has no lens only a small opening made with a needle into brass. The aperture in a pinhole camera is a photographer’s F260.

Self in Landscape and Dreamland are images taken with a bathroom hamper re-purposed as a pinhole camera. The camera, by its nature, creates spontaneity and intuitive thinking.

I had collected many findings in my visual journals over the years—magazine clippings—tickets, reproductions of art works, origami, etc. These oddments became stimulii for taking pictures in my backyard. I was intrigued with my own thoughts and feelings.

The pinhole camera became a perfect vehicle for recording these intuitively. In the darkroom I loaded the hamper with 11x14 black and white photo paper to capture the image.

Outside, like a child, I gathered images, organized a setting on my patio against a backyard, which had grown like a jungle around me; I interacted with them. The pinhole camera gave me license to “ghost image” moments. I could enter my images for a fraction of time and leave. I became a performer in my images as well as a recorder of them. I worked in a state of stream of consciousness.

While taking these extended moments, I absorbed the sound of birds, trees rustling, the smell of wind and birds flitting around while I stood in front of a large planter. I moved two pieces of birch bark onto the stage as a frame and held still for the 40 second exposure.

Dream Land (Visions of Endless Hope)was a two- minute exposure. I lay in the grass, with a Hawaiian floral shirt on. I superimposed a Xeroxed image from a Victorian Children’s book over me as if I were carrying trails of endless hope yet clinging to a rope throughout the exposure.

I hand colored these images with oils; as I did so, I would find other objects hinted at, which I formalized: birds, flowers and the sun.

My images are layered like in a dream. As with a dream, I cannot explain my images; but years later they do resonate with the viewer and me.

Joyce D’Amore describes his photographs as “a celebration of life in all its facets,” and says that when he’s working his feelings overtake his sense of reason and rationale.

“The word surreal is in itself surreal. There are so many ways to look at this art form as there are viewers. To me it means and expresses something different for each individual, according to his or her evolutionary moment. Just like almost everything else.

“When I create a surreal photograph I conceptualize in a way that I rarely do within my creative process. I want the images to make some sense. I strive to reach a spark of connectivity between the viewer and the image. I title my work as a pointer to the concept and to strengthen whatever connection can exist. It is a very pleasant mode of creation and I am planning to produce more of these images because I really love doing so."

“In Beyond the Egoic Mind, I try to convey the belief that the ego is a prison within the human mind, and the spirit is the prisoner (represented by the refrigerator door and the bird) in the world of forms. The dimension of freedom from form, which is part of the same concept, only becomes real and liberating after a state of awakening, or enlightenment, becoming one with the universe (represented by the young man’s eye).

Is your head spinning yet?

In Infancy Discovery I point to a tender phase in infancy when life feels very intense and yet so much is unknown, to be discovered."

The world at large is a strange and beautiful place. The worlds in our heads, in our visions and our dreams, are even more so. Through art we can share these worlds, and there might be no artform more immediate or malleable than photography.

Sign up for our email list

Find out about new art and collections added monthly